Part (2 of 3)

C.C.A. Journal Entry – Part 2 July Edition

Structured Analytic Strategies: From Situational Logic to Theory-Informed Forecasting

Welcome to the July edition of the C.C.A. journal. This entry builds on our earlier discussions about the recurring challenges facing professional analysts. In part 1, we focused on the roles of perception and memory in the analytic process. Analysts in specialist fields like consumer behaviour, law enforcement, and national intelligence, face many other cognitive challenges. In our earlier entries, we also examined the limitations of intuition driven analysis which can result in flawed assumptions. We provided examples of heuristic assumptions that have contributed to significant failures in criminal investigations, marketing campaigns, and intelligence assessments. These shortcomings often arise because analysts select evidence that confirms existing beliefs. They do this rather than systematically evaluating all available information.

This month, we shift our focus to the merits of structured evidence collection and the application of formal analytic strategies. The goal is to show how structured analytic techniques support high-quality assessments. These assessments are defensible, especially when analysts work with both open-source and confidential data. In this piece, we offer an overview of four core approaches employed by C.C.A. analysts to enhance critical and creative thinking, mitigate bias, and strengthen the reliability of their conclusions. These strategies include situational logic, theory-based reasoning, historical comparison, and data pattern matching. They are essential tools in producing robust, predictive, and context-sensitive assessments.

It is worth reiterating a key principle that underpins our work. While not all intelligence requires a formal assessment, every assessment necessarily involves some form of analysis. Without structured analysis, the decision-making process is at risk of being reactive, impressionistic, or unduly influenced by cognitive bias.

1. Situational Logic

Situational logic involves examining the unique set of facts, data, and contextual elements relevant to a specific case or scenario. This method is especially useful for assessing cause-and-effect relationships that are contingent upon immediate circumstances. For example, analysts use situational logic to evaluate how an individual behaves in abnormal conditions. They also use it under high-stress conditions in an unfamiliar environment. In contrast, when the goal is to predict behaviour, focusing on habitual patterns in familiar contexts is key. Theory-driven approaches are more appropriate in these situations.

Interpreting events through the cultural or ideological lens of the subject under analysis is a primary challenge with situational logic. It is necessary to avoid using the analyst’s own worldview. This issue, often referred to as mirror imaging, can distort conclusions if not properly addressed. Moreover, situational logic is limited in its ability to generalise from past cases. Its focus is on the specific and often unmatched features of the current scenario.

2. Theory-Based Reasoning

The second approach, often met with skepticism in applied settings is theory-based reasoning. Many analysts, particularly those outside the academic humanities, associate the term “theory” with abstraction or impracticality. Nonetheless, in the analytic context, a theory simply refers to a generalised explanation of behaviour. It is an explanation of outcomes derived from repeated observation of similar events.

For instance, authoritarian leaders often respond to civil unrest by deploying security forces. They do this to suppress dissent. This behavioural pattern is supported by theory. A theory implies a structured relationship between conditions (variables) and outcomes (conclusions). This relationship enables analysts to make informed predictions when direct evidence is limited.

Analysts must exercise caution when applying theory. Overreliance can lead to confirmation bias. This is particularly true when relevant data is overlooked in favour of theoretical consistency. Historical failures demonstrate the dangers of allowing theory to override contradictory evidence. These failures include the intelligence misjudgments preceding the 1973 Yom Kippur War[1]. They also include the 1979 Iranian Revolution[2] and the October 7th 2023 Hamas attacks[3].

In contemporary contexts, like election forecasting without reliable polling data, C.C.A. analysts often use theory-informed models. This includes analysing historical campaign trends, voter psychographics (e.g., using OCEAN personality dimensions), and identifying precedent-setting events that influence political attitudes.

3. Historical Comparison

When direct data is unavailable, drawing analogies from history can provide valuable insight. This method entails identifying relevant past cases involving comparable actors, locations, or circumstances. While history is not a deterministic predictor, well-matched historical analogues can provide a heuristic framework for understanding likely outcomes.

Analysts must be cautious about fitting current events into convenient historical templates. This mistake is sometimes called “putting the cart before the horse.” Rigorous scrutiny is essential to ensure that the historical parallels selected are appropriate. It is also crucial to account for key contextual factors before deriving conclusions.

4. Data Pattern Matching

Finally, data pattern matching, often associated with the “puzzle metaphor,” is a widespread analytic strategy. It is premised on the assumption that objective data analysis will naturally yield discernible patterns.[4] While powerful, this approach is inherently shaped by the analyst’s prior assumptions, perceptual filters, and interpretive frameworks. In short, data does not speak for itself.

The interpretation of data is unavoidably subjective, influenced by the analyst’s worldview, expectations, and cognitive biases. This does not invalidate the approach. However, it underscores the need for transparency. It also highlights the importance of critical reflection in the analytical process. It is also important to distinguish between information collection and information analysis. The former involves gathering a broad array of relevant material. This is an essential step. True analysis begins only when the material is examined in a structured, hypothesis-driven way.

Conclusion

This journal entry has introduced four principal strategies used by C.C.A. analysts in the pursuit of high-quality analytic outcomes: Situational Logic, Theory-Based Reasoning, Historical Comparison, and Data Pattern Matching. These methods are not mutually exclusive. In practice, effective analysis often involves a dynamic combination of all four. This combination is tailored to the specific demands of the task.

Our experience suggests that analysts tend to favour situational logic, perhaps due to its intuitive appeal and real-time applicability. However, underutilisation of theory and historical reasoning can result in analytical blind spots and misjudged predictions. Divergent approaches to analysis often create tensions between practitioners in the field. There are also tensions among desk-based analysts, policy consumers, and academic researchers. Each operates under distinct constraints and epistemic preferences.

At C.C.A., we emphasise the importance of perspective-taking as a critical competency. Our analysts recognise and adapt to the cognitive perspectives of diverse stakeholders. They also consider cultural and operational perspectives. This approach enhances the relevance and impact of their assessments.

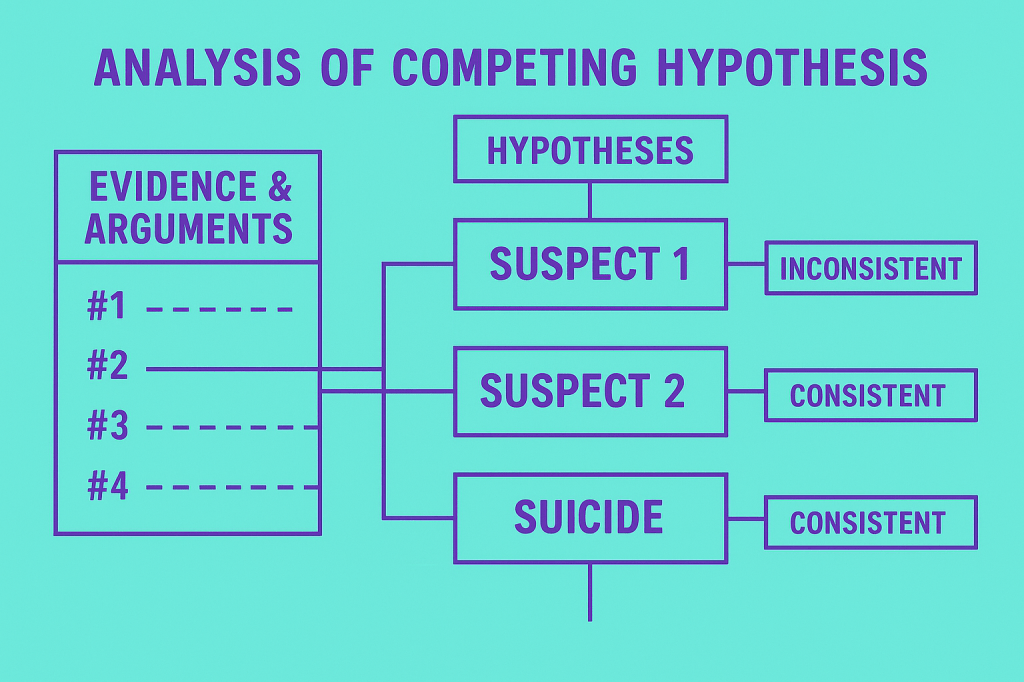

We thank you for engaging with our ongoing journal series, which is intended to enrich the practice of professional analysis. Our next entry will explore the relationship between data collection and hypothesis development. It will offer practical guidance on how to formulate and evaluate hypotheses. This will be achieved using a systematic, evidence-led approach.

If your organisation is facing a complex challenge, we invite you to contact C.C.A. Our analysts specialise in discreet, ethical problem-solving to help clients navigate some of the most intricate dilemmas imaginable.

[1] Moens, A., 1991. President Carter’s Advisers and the Fall of the Shah. Political Science Quarterly, 106(2), pp.211-237.

[2] Shlaim, A., 1976. Failures in national intelligence estimates: The case of the Yom Kippur War. World Politics, 28(3), pp.348-380.

[3] Barnea, A., 2024. Israeli intelligence was caught off guard: The hamas attack on 7 october 2023—a preliminary analysis. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 37(3), pp.1056-1082.

[4] Gozzi, R., 1996. The jigsaw puzzle as a metaphor for knowledge. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 53(4), pp.447-451.

Leave a comment