Why we often see what we expect to see based on our prior beliefs.

Harvard University decided to revoke her tenure. They accuse Professor Francesca Gino of academic misconduct. The allegations relate to a 2012 co-authored study. The research in question claimed that signing an honesty pledge at the beginning of a form increased truthful disclosures. This was as opposed to signing the pledge at the end. Harvard alleges that Gino manipulated the data to favour the preferred alternative hypothesis, undermining the null. Gino denies the allegations, asserting on her personal website that she neither fabricated nor knowingly altered the data.

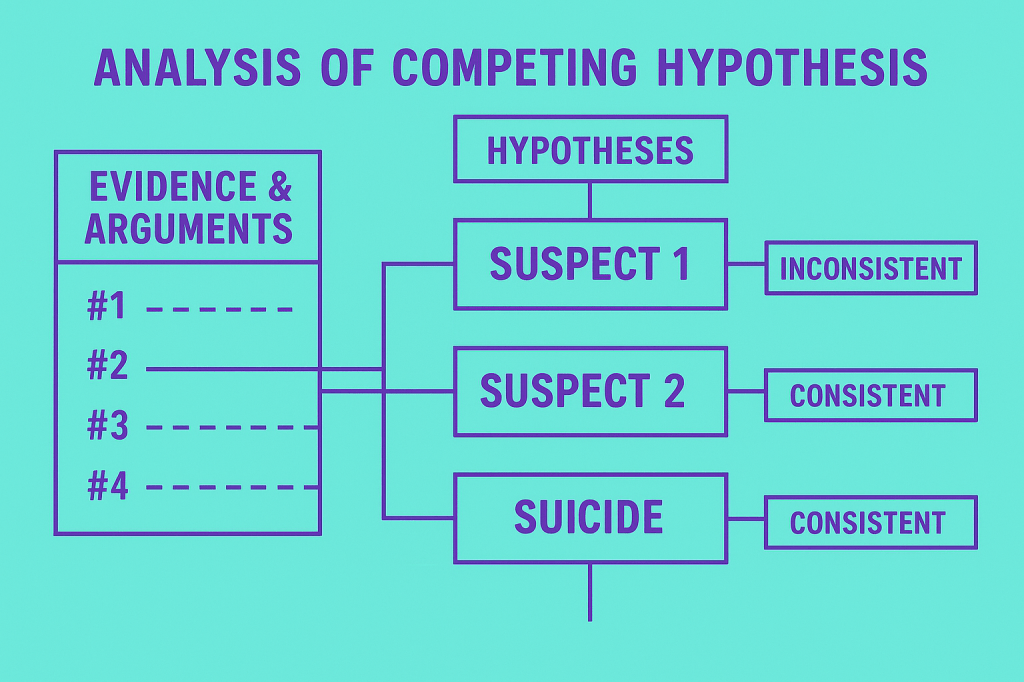

This controversy transcends individual culpability. It highlights the deeper vulnerability of the scientific process to both external pressures and internal cognitive biases. The case underscores a crucial point, whether or not Gino acted with intent. Human beings are not neutral processors of information. As we have earlier explored in C.C.A.‘s journal entries, we are all susceptible to confirmation bias. This is the tendency to privilege information that aligns with our beliefs. We also discount evidence that challenges them, even when that evidence is robust.

Scientific research does not occur in a vacuum. It unfolds within a system full of incentives. These incentives can distort integrity. They include the pressure to publish, career advancement, financial rewards, and the race to be first with novel findings. Journals often lack rigorous mechanisms to verify the validity or reliability of submitted research. The burden of proof falls largely on authors. Authors are themselves human—fallible, biased, and motivated.

Bias is not inherently malicious. It serves adaptive functions in everyday life, enabling fast decision-making in uncertain or high-pressure situations. Yet, in the context of research and analysis, bias can profoundly distort outcomes. While the term “academic misconduct” has a legal and procedural definition, the associated values—integrity, ethics, trust—are more fluid. They are socially constructed, contested, and interpreted through shifting cultural and institutional lenses.

True objectivity is a myth. All inquiry begins from a standpoint; what matters is how reflexively and transparently we account for it. Analysts and researchers must acknowledge prior beliefs. They must acknowledge cognitive tendencies. These shape how evidence is gathered. They influence how it is interpreted and reported. The discipline lies in recognising those biases—not erasing them but declaring them and controlling for their influence.

Whether Francesca Gino was consciously biased or unknowingly influenced by her own expectations, we may never know. However, the broader lesson remains. Scientific credibility is not secured by individual virtue alone. It is secured by cultivating systems and mindsets that reward methodological humility, transparency, and critical self-awareness.

Leave a comment