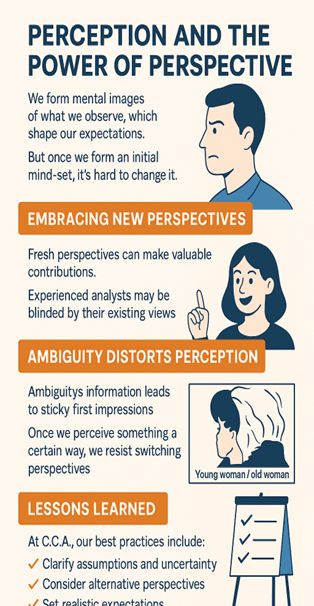

Perception and the Power of Perspective: Part 2

In our last post, we introduced the idea of perception, how we form mental images of what we observe, which then shape our expectations. In this post we will discuss how our mental models, once formed, have a powerful influence on how we interpret future events. We will give an example of how we often view problems drawing from past experience and embedding old thinking into new ways of thinking that creates a cognitive trap. The purpose of this post is to make us aware of a crucial challenge we need to work around; once our minds are set, it becomes very difficult to change them, even when new evidence contradicts what we originally believed.

Why We Struggle with the New and Unfamiliar

As humans, we naturally dislike uncertainty, gaps in our knowledge, and ambiguity. We tend to fit new information into our existing mental frameworks, even when the new data doesn’t quite belong. This tendency helps explain why gradual, evolutionary changes often go unnoticed, they’re simply absorbed into our old ways of seeing things. Let me share a personal example that illustrates the point about one of the pitfalls of our certainty about our mindsets.

When I first joined the Foreign Office as a specialist adviser, I was seen as an expert in my field. Early on, a new analyst was assigned to my team to help tackle a complex, long-standing issue we’d been working on for over two years. During her first briefing, we didn’t expect her to contribute, just to listen and learn. But to everyone’s surprise, she asked insightful questions that no one on the team had considered before. Her fresh perspective led to new lines of inquiry that ultimately helped us reach a satisfying resolution to a case we’d been stuck on for months.

That experience taught me a valuable lesson: sometimes, the fresh eyes of someone new can see what a seasoned team cannot. Experience, while invaluable, can also limit our ability to see things differently. Our mental models—formed over years—can blind us to new possibilities.

Why C.C.A. Analysts Constantly Shift Perspectives

At C.C.A., our research teams make it a point to reorganise and reinterpret familiar data to see problems from different angles. This is crucial in understanding how international audiences perceive events, campaigns, or products. We frequently ask: How might a different kind of consumer interpret this message?

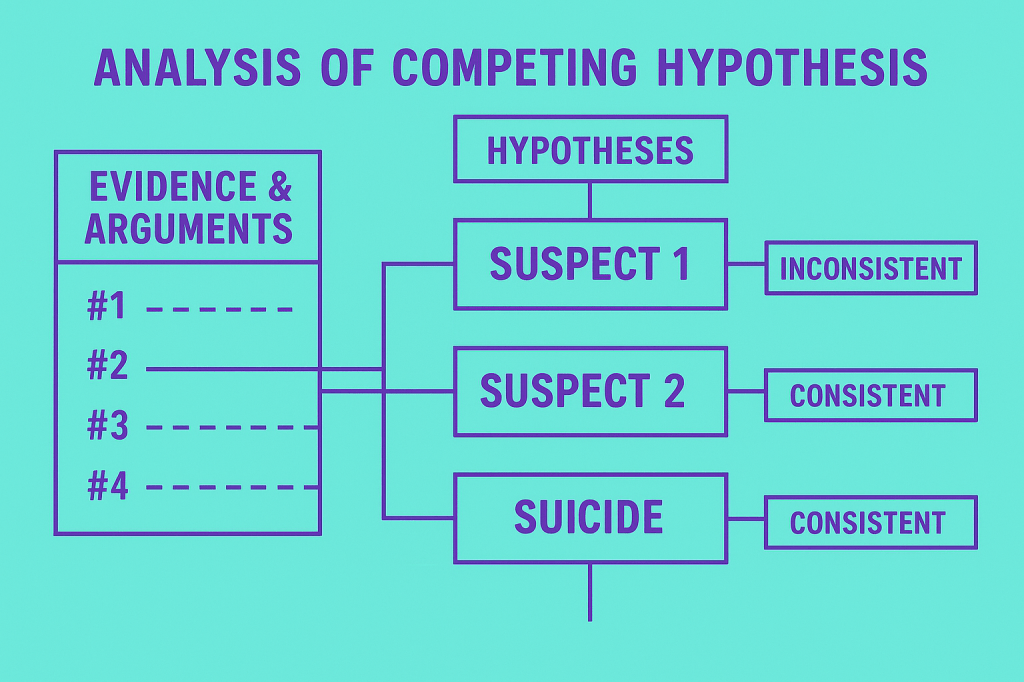

To illustrate, revisit the classic optical illusion below known as the “young woman/old woman” image (see Fig. 1). Depending on your perspective, you might see one or the other but rarely both at once. This is a powerful metaphor for how our minds work: once we perceive something one way, it’s hard to switch perspectives, even when shown clear evidence.

How Ambiguity Distorts Perception

Initial impressions, especially when formed in response to unclear or ambiguous information, stick in our minds. Even when clearer evidence becomes available, we tend to hold on to our original interpretation. The longer we’re exposed to unclear data, the more confident we become in our assumptions. This creates a bias: we fit new information into our original interpretation rather than revising it.

Why does this happen? Because it takes far more information to disprove a belief than it does to form one in the first place. It’s not that people can’t understand new ideas; it’s that our existing beliefs are hard to shake. We make fast (heuristic) judgments based on limited data, and those early impressions are remarkably persistent.

At C.C.A., we tackle this problem by deliberately suspending judgment. We train our analysts to remain open to new information, even if it challenges prior assumptions.

What This Means for C.C.A.’s Work

Understanding how perception works has direct implications for our analytic process—especially in high-stakes, high-uncertainty environments. We often have to make sense of fragmented data under tight deadlines. These are exactly the conditions under which perception is most likely to be distorted.

Some of our most interesting assignments involve bringing clarity to ambiguous problems. We approach them step-by-step, following the trail of evidence as it becomes available and avoiding premature conclusions. The more ambiguous the situation, the more important it is to remain flexible in our thinking.

Lessons Learned: C.C.A’s Internal Best Practices – We call them our CeCS

To manage these cognitive challenges, we’ve built 4 key practices (CeCS) into all our strategic brainstorming sessions:

- Clarify assumptions and uncertainty: Our internal reports spell out the assumptions we’ve made and the level of certainty we have.

- Encourage inductive thinking: We build our understanding gradually, drawing conclusions from the ground up.

- Consider alternative perspectives: We actively explore different ways of looking at the same problem.

- Set realistic expectations: We’re transparent with clients about the limitations of any analysis, so they can judge the quality of our insights fairly.

We conclude Part 2 of our series on perception. In this post, we explored how new information is often forced to fit into old mental models, how we tend to perceive what we expect, and how hard it can be to revise our views—even in the face of better evidence. We have shown how C.C.A overcomes this bias through our CeCS approach. In our next post series, we’ll discuss how memory is linked to perception and how together they shape the way we understand the world around us and how we embed this knowledge in our client campaign strategies. So stay tuned.

fig.1.

Leave a comment