Part (2 of 3)

Journal Series: The Scientific Method and the Analytic Process (Part 2)

Journal Entry: Disproving, Not Confirming – The Analyst’s Scientific Mindset.

In our earlier journal entry, we explored why an intelligence analyst’s memory is a pivotal factor in analytic performance. Memory doesn’t just support recall, it actively shapes analytic judgment, which must strive to be right for the right reasons. We examined the difficulty of unlearning entrenched schemata. Replacing them with new ones is comparable to correcting a flawed tennis swing after years of muscle memory. We also noted that long-held mental models can lead to cognitive inertia. This inertia limits adaptability in fast-changing environments. It also compromises analytic accuracy.

This week, we turn our attention to a foundational principle in analytic rigor: dis-confirmation over confirmation. In the 1960s, Sherman Kent promoted using the scientific method in intelligence work. He argued that impartiality and methodological skepticism were essential to filling informational gaps. These approaches also help in anticipating future developments.[1] His insight remains profoundly relevant.

In many intelligence and law enforcement settings, analysts still rely on non-scientific methods. They select the most plausible hypothesis based on surface alignment with the data. But this is not analysis in the truest sense. The scientific approach demands more. It actively attempts to falsify hypotheses. It does not seek evidence that merely confirms what we already believe to be true.[2]

Under the scientific model, the hypothesis that withstands the most rigorous scrutiny earns further consideration; weaker ones are discarded.[3] This is a more robust pathway to truth. Unfortunately, several flawed strategies continue to shape decision-making across the intelligence community.[4] These include:

The Good Enough Hypothesis – Settling prematurely on a plausible explanation without evaluating alternatives.

Incrementalism – Considering only minor variations of a preferred explanation, neglecting divergent perspectives.

Consensus Bias – Defaulting to the view that carries institutional favour or managerial endorsement.

Descriptive Overreach – Merely describing a situation without making a substantive analytic judgment.

At C.C.A., we advocate for systematic evaluation of multiple competing hypotheses (MCH). This approach promotes objectivity, reduces bias, and offers a more reliable understanding of current and future developments. Nevertheless, implementing this approach is cognitively demanding. Human reasoning, particularly intuitive or heuristic reasoning, struggles to manage the simultaneous evaluation of multiple hypotheses. As such, the problem must be externalised for clarity and validity.

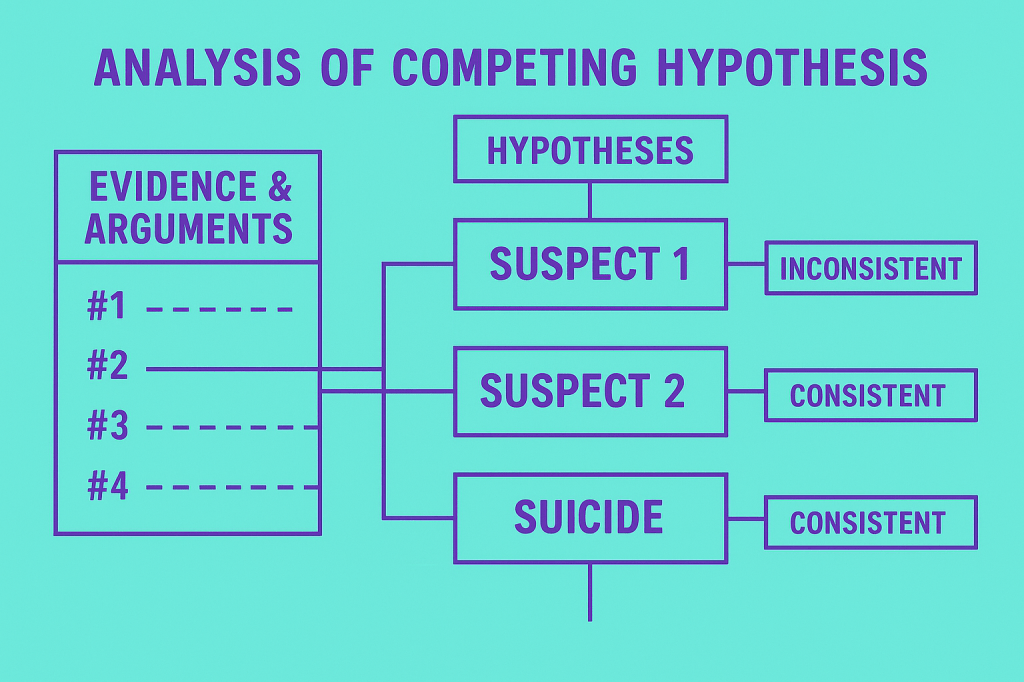

One effective tool for this is the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH). It is a structured eight-step method adopted by many intelligence agencies. Our own analysts at C.C.A. also use it. [5] The ACH model externalises the reasoning process, guiding analysts to critically test each hypothesis and seek dis-confirming evidence.

We encourage analysts to adopt this method. This is particularly important for those engaged in predictive analysis involving public safety, political forecasting, or market success. The goal is not to dismiss intuition entirely, but to balance it against structured reasoning. In predictive contexts, where the cost of error is high, relying solely on gut feelings is a professional liability.

Conclusion.

Analysts often fall into the trap of confirmation bias across intelligence, consumer behaviour, and strategic forecasting. They seek data that supports an instinctive answer and disregard inconvenient evidence. When preferred hypotheses are affirmed, there’s often a retrospective illusion of certainty: “I knew it all along.” When they’re not, evidence is dismissed or new hypotheses adopted without rigorous scrutiny.[6]

This intuitive style of analysis is driven by unconscious assumptions. It leaves judgments vulnerable to chance. It also relies on guesswork or being right for the wrong reasons.[7] At C.C.A., we believe this is not an acceptable standard for professional analysis.

That’s why we rigorously test our analytic processes, conclusions, and client recommendations. Post-project reviews and retrospective audits allow us to refine our methods and improve our outcomes. Whether advising on consumer marketing strategies, political risk, or reputation management, we uphold high standards of analytic integrity.

In our next journal entry, we’ll explore the role of different types of evidence. We will also examine the analytic methodologies our team employs. At C.C.A., we blend academic rigor with applied research. This approach provides clients with high-impact, evidence-based advice. It is effective when launching a product, crafting a campaign, or anticipating adversarial behaviour. Have a look at our website and see how we can help you achieve your ambitions.

[1] Davis, J., 2002. Sherman Kent and the profession of intelligence analysis. US Central Intelligence Agency, Sherman Kent Center for Intelligence Analysis.

[2] Hill, C., Memon, A. and McGeorge, P., 2008. The role of confirmation bias in suspect interviews: A systematic evaluation. Legal and criminological psychology, 13(2), pp.357-371.

[3] Laudan, L., 2013. Science and hypothesis: Historical essays on scientific methodology (Vol. 19). Springer.

[4] Dhami, M.K., Mandel, D.R., Mellers, B.A. and Tetlock, P.E., 2015. Improving intelligence analysis with decision science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), pp.753-757.

[5] Dhami, M.K., Belton, I.K. and Mandel, D.R., 2019. The “analysis of competing hypotheses” in intelligence analysis. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(6), pp.1080-1090.

[6] Akinci, C. and Sadler-Smith, E., 2020. ‘If something doesn’t look right, go find out why’: how intuitive decision making is accomplished in police first-response. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(1), pp.78-92.

[7] Strick, M. and Dijksterhuis, A.P., 2011. Intuition and unconscious thought. In Handbook of intuition research. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Leave a comment