Part (1 of 3)

Journal Series: Memory and the Analytic Process (Part 1)

In this series, we explore the vital role memory plays in analytical thinking and how our higher-order cognitive functions help us navigate complex problems. Understanding memory is essential because how we register, store, and retrieve information directly affects the quality of our analysis and decision-making.

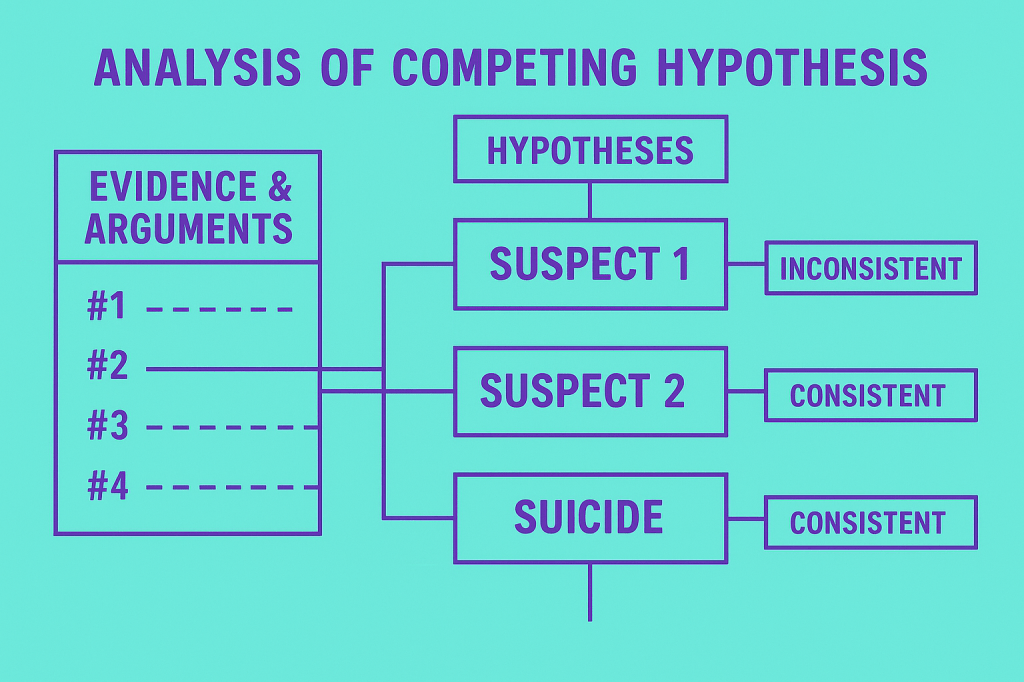

To simplify a complex and highly debated field, we focus on three interconnected but distinct memory systems as they relate to the analytic process:

🔹 Sensory Information Storage (SIS)

🔹 Short-Term Memory (STM)

🔹 Long-Term Memory (LTM)

SIS holds raw sensory input for a fraction of a second just long enough for the brain to begin processing it. STM then briefly stores an interpreted version of that input, allowing us to extract meaning, relevance, and significance. Only select information transitions into LTM, often unconsciously.[1] Critically, we can only retrieve what has been successfully encoded at earlier stages.[2]

Our memory functions as a dynamic network of neural connections, billions of neurons linked by synapses. Each new experience creates new neural “roads,” while repeated experiences reinforce and solidify these paths. Over time, deeply embedded patterns become difficult to alter. Once a mental “road” is well-travelled, like a habitual move in chess or cards, it can be hard to see the problem from a different perspective.

These neural networks form schemata which are structured clusters of meaning based on our experiences. For example:

A school schema may evoke memories of uniforms, teachers, playgrounds.

A university schema might include ideas of independence, activism, or campus life.

A failing State schema could involve concepts like government corruption, civil unrest, or economic collapse.

Schemas shape our perceptions, and in turn, our analytic judgments. If our schemas are outdated, biased, or incomplete, our conclusions will likely be flawed. Good analysis depends on the interplay between facts, context, and the mental frameworks we use to interpret them.

Additionally, our working memory, the cognitive space where real-time problem solving happens is severely limited. According to the “Seven ± Two” rule, we can only hold a handful of items in our minds at once.[3] This constraint makes it difficult to juggle all the necessary variables when analysing complex problems (e.g., political, legal, economic, and technical aspects of a threat actor’s intent and capability). That’s why external tools and structured methodologies are essential.

The key takeaway: Be aware of your mental “roads” and “maps.” Rigid thinking, rooted in past experience, can hinder the ability to see new solutions. Analysts must remain open to new data, challenge old assumptions, and be willing to redraw their mental maps.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll explore how C.C.A. analysts make informed judgments and argue for using the scientific method in analysis. We’ll also introduce practical strategies for improving reasoning in uncertain and ambiguous situations, because having the right strategies helps our analysts prioritise and process data effectively.

Thank you for engaging with our journal entries. We hope you find them insightful and thought-provoking.

[1] Batouli, H., Amir, S. and Sisakhti, M., 2019. Investigating A Hypothesis on The Mechanism of Long-Term Memory Storage. NeuroQuantology, 17(3).

[2] Norris, Dennis. “Short-term memory and long-term memory are still different.” Psychological bulletin 143, no. 9 (2017): 992.

[3] Batouli, H., Amir, S. and Sisakhti, M., 2019. Investigating A Hypothesis on The Mechanism of Long-Term Memory Storage. NeuroQuantology, 17(3).

Leave a comment