C.C.A., believe that sharpening the mind is the most powerful way to sharpen analysis.

In our earlier C.C.A. Journal entries, we explored the foundational importance of perception. It is a concept often overlooked. Yet, it is vital for anyone working in consumer research, intelligence, or complex decision-making environments.

We discussed the necessity for analysts to be aware of human perceptual limitations. This is crucial when processing ambiguous or incomplete information. It is especially important under pressure or when deception has to be considered during analysis.

Multi-modal emotion recognition is a growing area of research. It attempts to extract deep features. These features emulate the human brain’s perception of emotional cues. This new field of perceptual research is in its infancy. Yet, its rapid growth shows the essential role perception plays in engaging our high order critical thinking skills.[1]

How familiar is the following scenario: An analyst or clinician makes a rapid judgment. This judgment is later reinforced by selective evidence gathering diverging from the scientific method. It is a judgment often influenced by senior officers or by institutional consensus.

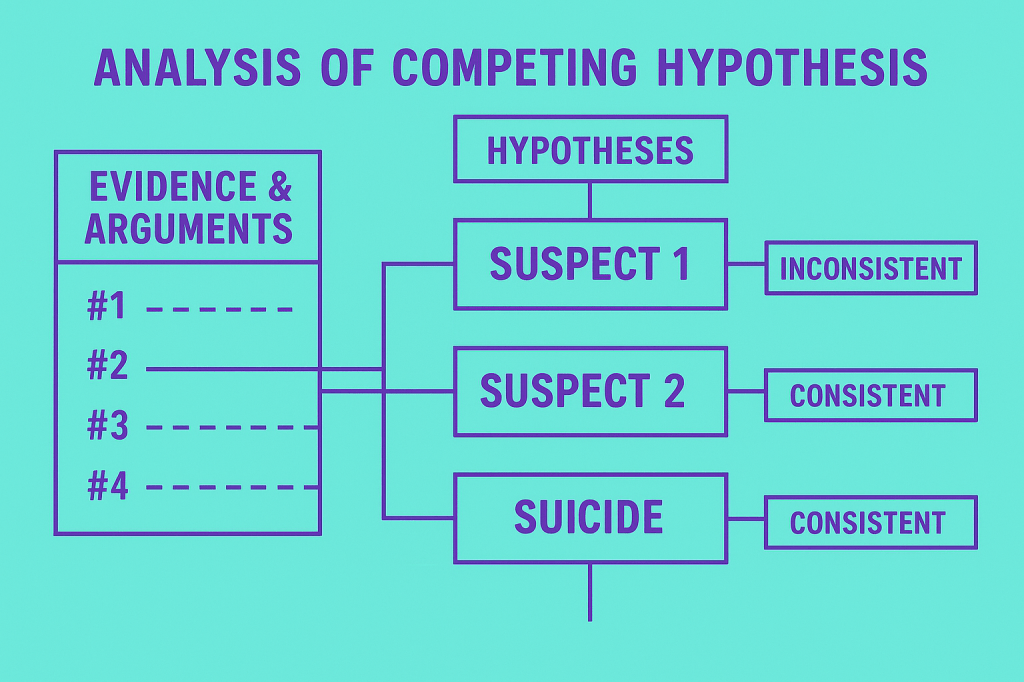

The develops tunnel vision, they are unable or unwilling to seriously consider any other less popular scenarios. A hasty interpretation begins. It then solidifies into a strategic or tactical position. This sometimes has catastrophic consequences to life and liberty. We highlighted this cognitive chain reaction in our earlier articles on Perception Parts 1 & 2.

[1] Yu, L., Li, X., Luo, C., Lei, Z., Wang, Y., Hou, Y., Wang, M. and Hou, X., 2024. Bioinspired nanofluidiciontronics for brain-like computing. Nano Research, 17(2), pp.503-514.

The Problem of Fragmented Thinking in Analysis

Much of this stems from what psychologists’ term anchoring and confirmation bias. These are cognitive shortcuts involving judgments based on heuristics and the first available fragments of information. Academics make interpretations through the lens of existing beliefs. Experienced medical practitioners, intelligence analysts, police investigators, and high profile advertising agents interpret symptoms and evidence through biases.

Professional analysts often rely on institutional worldviews.[1] Instead of a systematic, holistic approach to sensemaking, Law enforcement officers rely heavily on intuition. This intuition is sometimes referred to as the ‘policeman’s nose’, gut instinct, or “I’ve seen it all before.“

Then a powerful term is used to describe particular information. This information is used to buttress fragmented, belief-driven approaches of processing. It often masquerades as rigor. The term is intelligence.

We’ve all heard phrases like, “The intelligence says” or “We have new intelligence to suggest…” But too often, this simply means “We have been given new information”—not necessarily derived from intelligence analysis. Referring to raw information as “intelligence” can make it sound more credible.

It can be more actionable. Nevertheless, it glosses over the uncertainty and ambiguity. It also ignores the verification that true intelligence work demands.

[1] See Sætrevik, B., Seeligmann, V.T., Frotvedt, T.F. and Keilegavlen Bondevik, Ø., 2024. Anchoring, confirmation and confidence bias among medical decision-makers. Collabra: Psychology, 10(1).

What Is Intelligence and why is it important?

At C.C.A., we are deliberate with our language. Words matter—not just for clarity, but for analytical precision. We consider “intelligence” a meaningful concept only when information has been tested.

It must be contextualised and shown to reduce uncertainty in meaningful ways. As Wilhelm Agrell wrote in an article back in 2002: “When everything is intelligence, nothing is intelligence.” [1] The article explains that intelligence requires the rigor of a scientist. It also needs the curiosity of a journalist who verifies sources.

True intelligence thus exists between knowledge and uncertainty. It lives between what we know. It also lives between what we think we know and what remains unknowable.

[1] Available at: https://www.cia.gov/resources/csi/studies-in-intelligence/archives/when-everything-is-intelligence-nothing-is-intelligence/

Perceptions Resist Change—And That’s the Problem

Cognitive psychology shows us that once humans form an opinion, we stick to it. We are unlikely to change, regardless of new evidence that refutes the original view. Our perceptions resist change.[1]

We assimilate new information into pre-existing narratives and dismiss or downplay conflicting data. This rigidity is responsible for many of the costliest analytical failures: in political forecasting, economic trend prediction, and conflict analysis.

When analysts and decision-makers are convinced they “know what’s going on,” they become blind to signals that contradict their assumptions.

This isn’t just a professional hazard—it’s a human one.

[1] Yuan, S., Bai, J., Li, S., Ma, N., Deng, S., Zhu, H., Li, T. and Zhang, T., 2024. A multifunctional and selective ionic flexible sensor with high environmental suitability for tactile perception. Advanced Functional Materials, 34(6), p.2309626.

Why Memory Matters

In our upcoming entries that start on 19th May 2025, we’ll dive deeper into the link between perception and memory. This connection is often overlooked but crucial for analytical accuracy. There are two core memory functions impacting on analytic quality:

- How information is stored in long-term memory, and

- The accessibility of past experiences and knowledge.

Understanding how memory works gives us the ability to enhance our creativity. It helps us stay open to different viewpoints. It also allows us to avoid falling into cognitive traps.

At C.C.A., we use a diverse set of research methodologies. We also use analytical tools to manage data. Yet, our most powerful resource is still the human mind. When cultivated properly, it can outperform even the most advanced Natural Language Processing (NLP) and computational systems.

Elevate Your Analysis

C.C.A’s mission is to give those who entrust us with their campaigns or projects precise and targeted advice. We take an inward approach. We equip our analysts with cognitive tools. We offer scientific grounding.

Cognitive tools help analysts make better decisions in uncertain environments. In the coming entries, we’ll signpost you to some practical skills and techniques. We use these techniques to overcome bias. We also use them to improve perception and harness memory to its fullest potential.

We like to share our insights. We reach outside of our protected environment to stay connected. Why not join us in becoming more than just consumers of information. You can join us to become a more disciplined, self-aware, and truly insightful analyst.

Leave a comment